Contact MeUse the contact form at the bottom on almost all the pages on this site or let's have a Other ways to Support My WorkSubscribe to Insight-Live.com. It is about doing testing and development, not letting information slip away. Help Me on Social

Login to your online account Chemistry plus physics. Maintain your recipes, test results, firing schedules, pictures, materials, projects, etc. Access your data from any connected device. Import desktop Insight data (and of other products). Group accounts for industry and education. Private accounts for potters. Get started. Download for Mac, PC, Linux Interactive glaze chemistry for the desktop. Free (no longer in development but still maintained, M1 Mac version now available). Download here or in the Files panel within your Insight-live.com account. What people have said about Digitalfire

What people have said about Insight-Live

| March 2026: We are doing major upgrades to code here, please be patient regarding any issues. If any page is not working for a period of hours, please contact us. Thank you. BlogA comparative glaze opacity test in a tile lab:The way to minimize Zircon

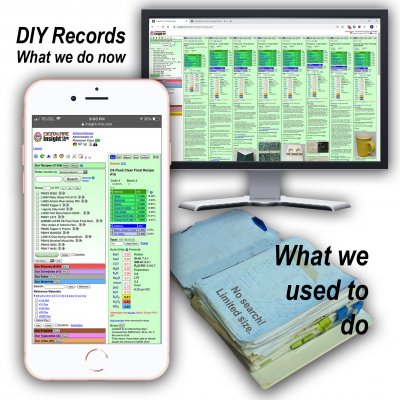

Strips of the same glaze recipe, each containing different percentages of zircon opacifier, have been applied across both a dark-burning body and a white engobe. While it is difficult to measure the absolute degree of opacity from a photo like this, the side-by-side comparison makes differences easy to see. Tests like this demonstrate that simple visual comparisons can often be as useful as instrument measurements when evaluating glaze opacity. Colorimeters measure Lab* color values, not opacity directly. This test is really about visual hiding power, which instruments don't always capture well. Context: DIY the commercial glaze.., Opacity Saturday 7th March 2026 Messy binders don't have a "search button"And they hold a limited number of pages

Are your records in a messy binder? Binders don't have "Search" buttons. Side-by-sides. And many DIYers would generate a binder full in a year. But how does one even start to organize? Context: The New 2 2.., Digitalfire Insight-Live Friday 6th March 2026 DIY the commercial glaze on mug #1:You must consider five factors to make it work

The mug on the left, #1, is a commercial brushing glaze. It is opaque enough to cover this red-burning clay body. It shows the desired effect. That depends on the fact that opaque glazes stretch thinner on the sharp edges of incised designs. If they have enough melt mobility and are applied right, the effect is amplified. This potter is attempting to mix her own DIY equivalent as a dipping glaze, adding 4% tin oxide to a transparent base glaze in #2 and zircon (a higher percentage) in #3. As you can see, the effect is not working as well, and there are several reasons: Context: A comparative glaze opacity.., Opacity, Opacifier Thursday 26th February 2026 Step-by-step to do a formula-to-batch in Insight-Live.com

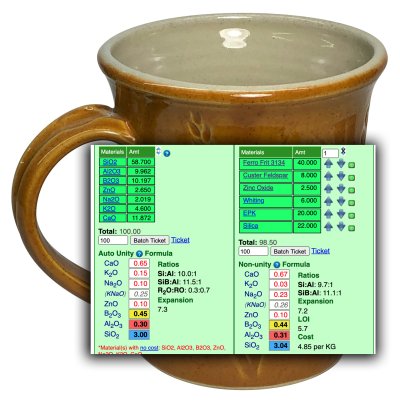

Insight-live does not automate formula-to-batch calculations, but it does assist in doing them. And it provides the tools to create an audit trail of test results, pictures and notes and a path to document subsequent adjustments. Along the way, you gain material knowledge and intuition. In this example, we derive the recipe of materials needed to source the oxide formula of a zinc clear cone 6 glaze (sourcing the oxides needed using a Ferro frit and other common raw materials). We'll create the target in a panel, start the batch in a panel beside it, supply the B2O3 from a frit and then the fluxes from feldspar, zinc and whiting. Then finish by rounding out the Al2O3 and SiO2 from kaolin and silica. The picture below shows the panels, the original target formula on the left and the final derived recipe on the right. The derived transparent glaze is on the inside of the mug and the outside is G3875, another zinc clear with iron and chrome added to produce the orange. Context: How to choose ceramic.., Click here for case-studies.., A formula to batch.. Thursday 19th February 2026 Here is why Albany Slip was hard to use: Crawling

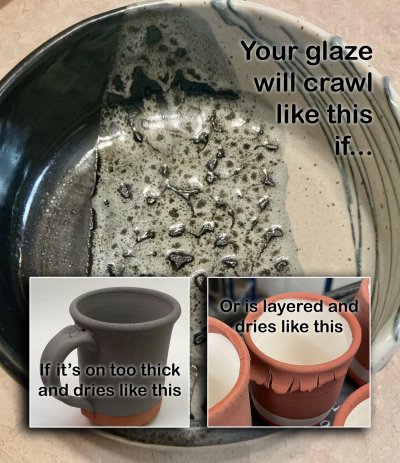

This glaze is 85% Albany Slip and 20% Ferro Frit 3195. These bisque tiles were dipped in a brushing glaze version of it (just water and powder). The glaze is applied quite thin on the front tile and thicker on the back one. The material gelled slurries and required a lot of water to make them thin enough to use. For assured success, this or any glaze that had a high percentage required mixing the raw Albany Slip with a calcined Albany Slip (which people had to make on their own). Context: Albany Slip, Melt fluidity and coverage.., Shrinking glaze peeling glaze.., Six layers 85 Alberta.., Crawling Wednesday 18th February 2026 Multilayer crawling

Oil-spot effects depend on being able to layer glazes. Normally, a black underneath and matte white over top. Using dipping glazes is obviously advantageous for this type of piece; the second dip covers the other half and creates the double layer needed. But dipping glazes contain clay in the recipe (almost always kaolin or ball clay), it satisfies multiple needs: It suspends the slurry, hardens the drying glaze, and supplies critical Al2O3 to the chemistry. The upper glaze here is a matte; so it needs extra Al2O3, which means it likely has extra clay. 20% kaolin (non-plastic like EPK, Grolleg, NZ) is about the maximum or the glaze will shrink too much when drying. If extra Gerstley Borate is added, then it will be worse. Drying cracks are the result when the fragile body-bond of the lower one fails to withstand the stresses of being rewetted and tugged upon by the upper layer being applied and drying. When the cracked double-layer begins to melt, it pulls itself into islands, leaving bare body between. That is called "crawling". Context: Glaze Layering, Crawling Tuesday 17th February 2026 Tile stacking in an electric kiln - Fingers crossed!

Small-scale operations everywhere are making tile like this. Most use plastic clay intended for pottery, which introduces more drying shrinkage, complicating drying them flat. Stacking them in the kiln can be a game of chance. Stacked too tightly and they crack (mostly because of quartz inversion). Stacked to loosely and most of the energy goes into heating the shelves and stackers. Using a clay with minimal large quartz particles is the best way to avoid dunting, however that is also a balance since such clays are more difficult to fit glazes to (without crazing). Context: Tile having angular shape.., An unevenly cooled tile.., It possible to make.., A plastic pottery clay.. Tuesday 17th February 2026 Stains are better in black DIY glazesUse 5% stain instead of 15% metal oxides

Consider the hazards and hassles before choosing a black matte or gloss recipe that has high individual or combined percentages of manganese dioxide, cobalt or nickel. Context: Ceramic Stain Toxicity Label.., Two cone 6 black.., Heres evidence that using.., Ceramic Stain, Toxicity Monday 16th February 2026 A plastic pottery clay for rolling ceramic tile:Not a crazy idea when it can do what this can!

This is the dolomite body recipe L4410P (a development version of Plainsman Snow). It is monoporosa tile on steroids; this body has zero percent firing shrinkage at cone 04! Predicting the final size and keeping that size consistent is much easier with such bodies. I have measured its drying shrinkage as 6% (doing our standard SHAB test). The final size needed is 20.5 cm square. Thus, I calculate the cut size to be 20.5 / (100 - 0.06) = 21.8 cm (or 20.5 / 0.94 = 21.8 cm). To keep these flat, we put them between sheets of drywall; the process takes 2-3 days. Since no change in size occurs during firing, this body has another big advantage: Tiles stay flatter during firing (a major problem with tile production). While making wall tile using a plastic pottery body is not something for industry (especially because of the space requirements for drying), for artisans working on a small scale, a body made by mixing super plastic ball clay with dolomite produces amazing working and tactile properties. The bonus is that they work so well at low temperatures, where there are so many glazing options. Context: Monoporosa or Single Fired.., QRCode mounted on Plainsman.., Tile stacking in an.., Tile that is actually.., Ceramic Tile Sunday 15th February 2026 This boron blue effect depends on three things:A dark body, variations in thickness, the right chemistry

This is G2826A3, a transparent amber glaze at cone 6 on white (Plainsman M370), black (Plainsman 3B + 6% Mason 6666 black stain) and red (Plainsman M390) stoneware bodies. When the glaze is thinly applied, it is transparent. But at a tipping-point-thickness, it generates boron-blue that transforms it into a milky white. Glazes that are very glassy but on the edge of structural instability do this. So they are not good for functional ware. Context: A pottery glaze that.., Boron Blue, Glaze thickness Saturday 14th February 2026 |

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy